1:26:25

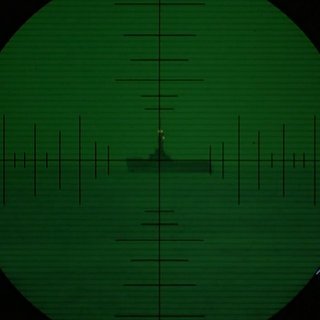

He looks like a moron, and he always has. Schoolyard nicknames and unkind uncles made that clear to him, pointing out his braying laugh and bug eyes and teeth like tombstones. It took a long time before he was big and angry enough to fight back and by then he believed it. As the submarine deck bucks and lurches underneath him, though, the shock seems to double his IQ.

There are thirty men on the submarine as it explodes. He knows twenty-two by name and regards six as friends. Take Gregory. Gregory is a decent guy. He doesn’t talk much, but doesn’t not-talk either, you know? Somehow they’d developed this stupid way of acknowledging each other. The usual macho nod evolved into a random dance of facial tics. Gregory could make his eyebrows move independently: left / down, right / up, vice versa. He could even roll them in a kind of quizzical Mexican wave. It was goddamn hilarious.

Sure, he finds it sad that Gregory’s dying right now, but it’s not what makes him ignore the water surging up from around his waist to under his chin. Choosing this life and then acting all shocked when things go wrong? All dainty and horrified? That’d be ridiculous. Like pointing and screaming when the seasons change. He wanted more time, but this was all the time he had. That’s fine.

It’s the third thing that has him sketching numbers in the water with his fingers. The thing he and Gregory created. Something other than either of them, born from their goofy interaction, the way they were only around each other. It dies too.

He’d never had much imagination. If you’d asked him to picture a sunset he’d barely manage to summon up a straight line bisecting a circle. All that changes when he feels the water press against his lips and thunder across his ears. He can see it: Venn diagrams in red and blue, the vivid overlapping purple fading first. No one will mourn what he and Gregory shared because no one knew it existed. He can hear it, too. Abacus beads clack between his ears. I counted wrong, he thinks.

Every man on board adds up to more than himself. Griffin’s different when McDonald’s fighting next to him: less berserk, more deliberate. Price and Perez and Taylor are relentless showmen – only ever inches away from an arm-wrestle – but they sync into quiet conversation whenever in the same room. And when Walker whispers goodnight to his goddaughter on the phone, mumbling her pet names, he’s someone new. Even his eyes change colour.

Actually, that might be the oxygen deprivation talking. His lungs were filled with napalm until a moment ago, when he opened his mouth and took a deep swig of filthy water. Now he feels a lot better. He’s floating in soft light. He can no longer hear panic echoing off the sub’s walls. Just strange clanks and booms like a sea-monster’s song.

Who knew drowning would make him a poet? This morning he was a murderous idiot dancing around in a dress. Now visions bloom before him. He sees the shimmering ghosts forged between every man on board. All thirty men are dying, but between them they made sixty, or a hundred, or more. Thirty suns rise, flinging themselves out of the sea and falling down in pieces, landing on mothers and son and girlfriends and old, ignored friends, becoming the crisp spheres of simulated nuclear detonations.

These men’s deaths impact out all over the world. He can see the truth of it glowing brighter and brighter as his own thoughts dim and drown. It’s a mass exorcism. All those shared half-lives wiped out in silence. No, he thinks, the word stuttering as he flickers in and out of consciousness. It’s worse than that. Some kept trophies of their kills like driver’s licenses, or severed ears, or small scars cut down their own arms. He just had a neat running tally in his head. He sees those numbers clock from two digits to three, four, five, all on fire and storeys-tall. Counting fractions, he’s killed more than cholera.

He’d scream if the idea of air wasn’t a distant memory. He yanks at his shirt and exposes a name tattooed across his collarbone, hard to read upside down and through dark water. He feels about a dozen whiskey’s drunk, thoughts sluggish and warm. He tries to picture her face. It doesn’t come. Instead he sees what they created together on their best days – small gestures and shy charm and loyal, vicious love – and he sees what they made at their worst. He doesn’t want to know. He just wants to drown.

Mercifully, his visions wilt and wash away. His lips part over his tombstone teeth and his eyebrows relax, one resting a little higher than the other. He dies alone. They all do. The only thing between them is water.

1:30:49

His wife will be handed the key to a safe deposit box. Inside she will find more money than she’s ever seen and diamonds he scored years ago but could never bring himself to sell. She’ll also see three handwritten letters: for her, for his brother, for his father. They all start: I am not the man you thought I was. He hadn’t finished a book since high school – it’d been something about talking animals – but he worked hard writing these letters and swapped new drafts for old every few months. Last visit, he’d wasted time slowly dripping the diamonds from their velvet bag into his cupped hand. He should’ve been proofreading, pawing through a dictionary. He should’ve made sure those letters were perfect. The diamonds weighed nothing.

1:31:02

Getting shot hurts less than expected. Less than when he’d put a nail through his foot working in his yard, its point all rust and blood; less than when that bitch kneed him in the balls after he’d walked her home at four in the morning and he’d thrown up on her door as she slammed it; less than when he ignored tonsillitis for so long even swallowing spit made his eyes water. The impact of the bullet shoves him back, though, and reminds him of when he used to be bullied sideways into walls and lockers. But I won, he thinks, smirking. I caused more pain than I ever felt. Now he’s dying, nothing can turn that black to red again.

1:31:11

When your throat’s torn out in front of your eyes, it leaves you leaking questions. Is that even possible? With his bare hands? How long can I live without a throat? Will he just throw it away now? Or will he keep it? Will he take it home and preserve it in a jar? Will it sit on a high shelf and gather dust? Does this killer have a son, and if so, will that son one day find the jar? Will he take it down and smear away the dust? Will he shake it? Peer through the formaldehyde? Will he press his ear to the glass? And will the throat inside stir, trembling, sensing his presence? Will it whisper to him? What will it say?

1:31:17

He knew his first victim so well – long story – it would’ve been suspicious not to go to the funeral. He sat in the back row of the church and cried and cried. He’d barely turned sixteen. (If he’d still had the gun on him that day, instead of feeding it to a storm drain? Who knows what he would’ve done?) But then the preacher told them all about God’s plan. How everything happens for a reason. “We’re all just a machine made of human parts!” the preacher said. It’s been an enormous comfort to know there was another reason, a divine reason, for every man he’d killed since. I’m ready, he prays, pitching forward, blood drooling from his chest. Tell me why.

1:34:34

He saw her while watching Saturday morning cartoons: hips of dynamite, bombs for eyes, fashioned to lure Bugs Bunny’s enemies to explosive ends. She made something itch down in the folds of his brain. He blames the itch for why he hears violins as the leftovers of dead cats and dead horses scraping together; why he sees men and women as sacks of blood, eager to be split and spilled. The world’s always been in pieces. Ten minutes ago he decided to kill millions with Tomahawk missiles and didn’t feel a thing – until the knife punctured his skull. Now all he can feel is how close the blade is to his itch. So close. The cold tip’s almost grazing it. Just a little deeper. Please.

0:00:00

He dies an old man, which surprises him, and alone, which does not. He’d made too much dinner again. After all these years, it was still hard to cook for one once you’d cooked for a whole ship. (The scraps will go to the wild dogs outside the cabin. He refused to name them – even the one with the patch.) Now he tries to stand, but each day his body finds some new way to betray him. He can’t blame it. He’s more scars than skin. The faces of those he killed are long gone, too: it might’ve been one man he kept putting in the ground, back from the dead, again and again. He tenses a fist, just to see if he can. He never lets it go.